« What is to be done? »

- curated by Óscar Faria

- Simógrafo, Oporto, 2016/17

- solo show:

- video, photography, drawing, performance

“What is to be done?” “Chto Delat?” Asked Nikolay Chernyshevsky in a book that came in response to “Fathers and Sons” of Ivan Turgenev. Published in 1863 the story features Vera Pavlovna, who tries to escape an arranged marriage through the conquest of her economic independence. It includes a political dimension: the author defends the creation of small socialists cooperatives based in peasants communes. Written in prison, the novel divides the opinion of readers like Lenin, Kropotkin and Rosa Luxemburg, advocates of the text, and Dostoyevsky, who later writes “Notebooks of the Underground” in response to the utopian and utilitarian ideas and a novella of a text marked by the growing industrialization of Russia.

It is however with Vladimir Lenin’s pamphlet “What is to be done?” (1902) that this question will become a trope still in need of an answer. With the subtitle “Burning questions of our movement”, this work includes this excerpt: “Freedom’ is a grand word, but under the banner of freedom for industry the most predatory wars were waged, under the banner of freedom of labour, the working people were robbed. The modern use of the term “freedom of criticism” contains the same inherent falsehood. Those who are really convinced that they have made progress in critical scholarship would not demand freedom for the new views to continue side by side with the old, but the substitution of the new views for the old. The cry heard today, “Long live freedom of criticism”, is too strongly reminiscent of the fable of the empty barrel.”.

The poet Ivan Krylov described the fable of the empty barrel: two barrels, one full, the other empty, fall from a cart into the streets. When they hit the floor, the full barrel makes less noise than the empty. The metaphor has its echo in a relevant political question in the context of that time, closing a critique to the “revisionists”, who cried loudly for the freedom of criticism, an inconsequential appeal though, because it has no ideas.

Lenin writes: “Some of us scream: “Let us go into the marsh! And when we begin to shame them, they retort: What backward people you are! Are you not ashamed to deny us the liberty to invite you to take a better road! Oh, yes, gentlemen! You are free not only to invite us, but to go yourselves wherever you will, even into the marsh. In fact, we think that the marsh is your proper place, and we are prepared to render you every assistance to get there. Only let go of our hands, don’t clutch at us and don’t besmirch the grand word freedom, for we too are “free” to go where we please, free to fight not only against the marsh, but also against those who are turning towards the marsh!”

“What is to be done?”, this has also been the question discussed by two philosophers, Alain Badiou and Jean-Luc Nancy. Let us focus on the last, who this year launched a book called precisely “Que Faire?”: “Time urges because the task is long... Caught up in a movement that began to move mountains, the worlds, forces, and forms in the likeness of what regularly revolves and reshapes the river, we experience an urgency: that of doing and thinking in order to be able to do. (...) It is necessary to plunge into this river that is never the same, diving and feeling the movement of the river bed, the movement of the banks, the force of the current. And try to keep the spirit far away in the sea, where the river reaches.”

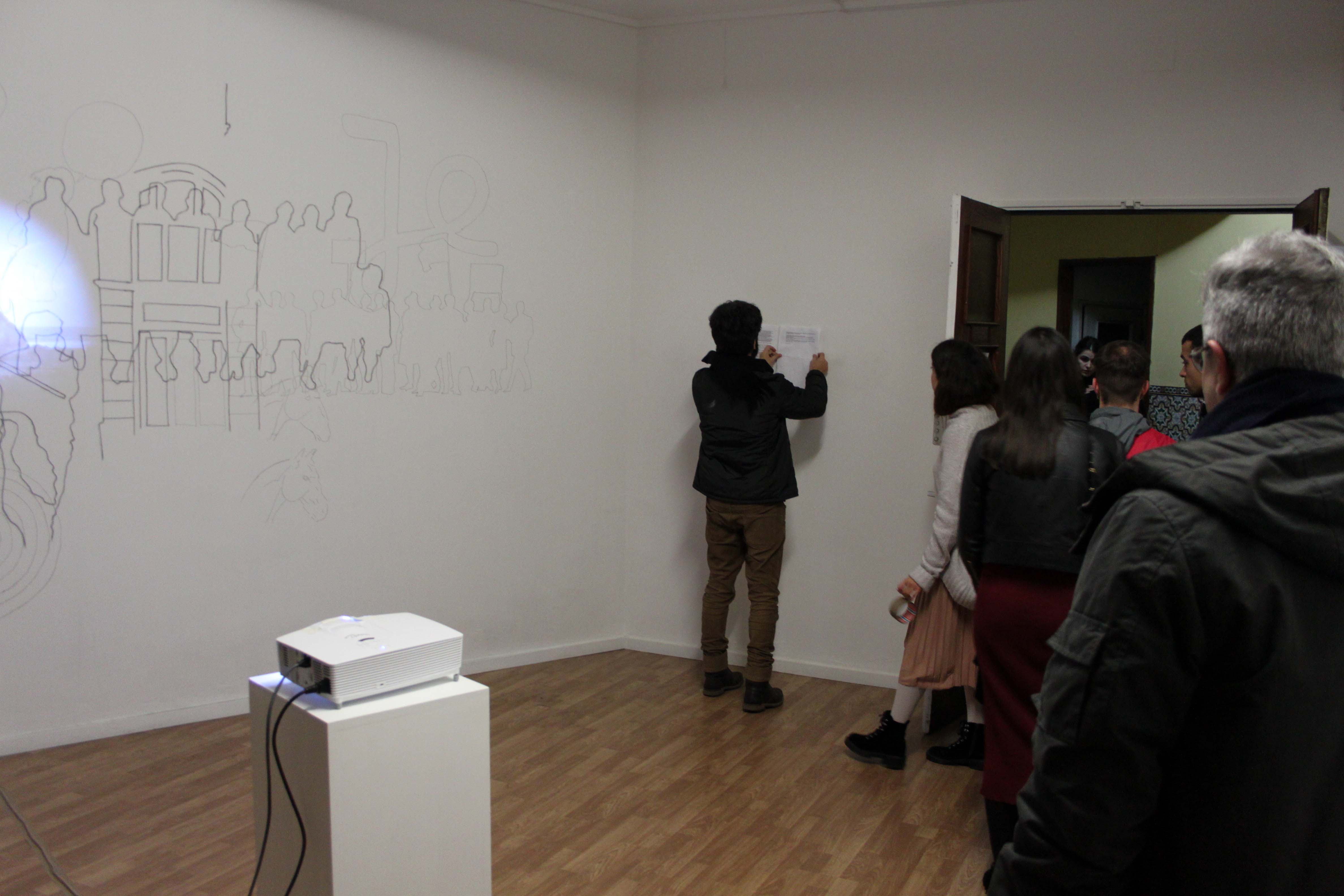

It was Ângelo Ferreira de Sousa who translated these words to Portuguese. It is him who propose to us to think the question “What is to be done?”, title of his exhibition at Sismógrafo, starting from a backdrop of more than 150 years. Without offering a solution to the problem, the author reveals five unpublished works through which we can find echoes, not only from the reflections of Lenine, Marx, Badiou and Nancy, but also evocations of Godard’s cinema – “Pierrot le Fou”, of Marker’s – “La Jetée” and of Assayas’s – “Carlos”. Video, drawing – a mural -, photography, performance and translation are the material from which he approaches this question, which we still do not know how to respond satisfactorily. Declining the verb suicidar (to commit suicide) in Portuguese from Portugal and in Brazilian Portuguese, without the spelling agreement and in chorus; reading a text out loud, changing roles, genres and languages; failing successive attempts to put a plastic bottle to fly, but insisting on this possibility to overcome destiny; drawing a line of questions and answers passed to images inscribed on a wall – and these drawings are already a crowd; singing with Karina and Belmondo, in shades of blue and red, parrot on the shoulder, on the run, always on the run: “What is to be done? I don’t know what is to be done!”

It is therefore necessary to dive into the river, to fight the marsh. As Samuel Beckett wrote at the end of “The Unnamable” written in 1949: “(...) It will be the silence, where I am, I don’t know, I’ll never know: in the silence you don’t know. You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on.”

Will we someday know what is to be done? [Óscar Faria]

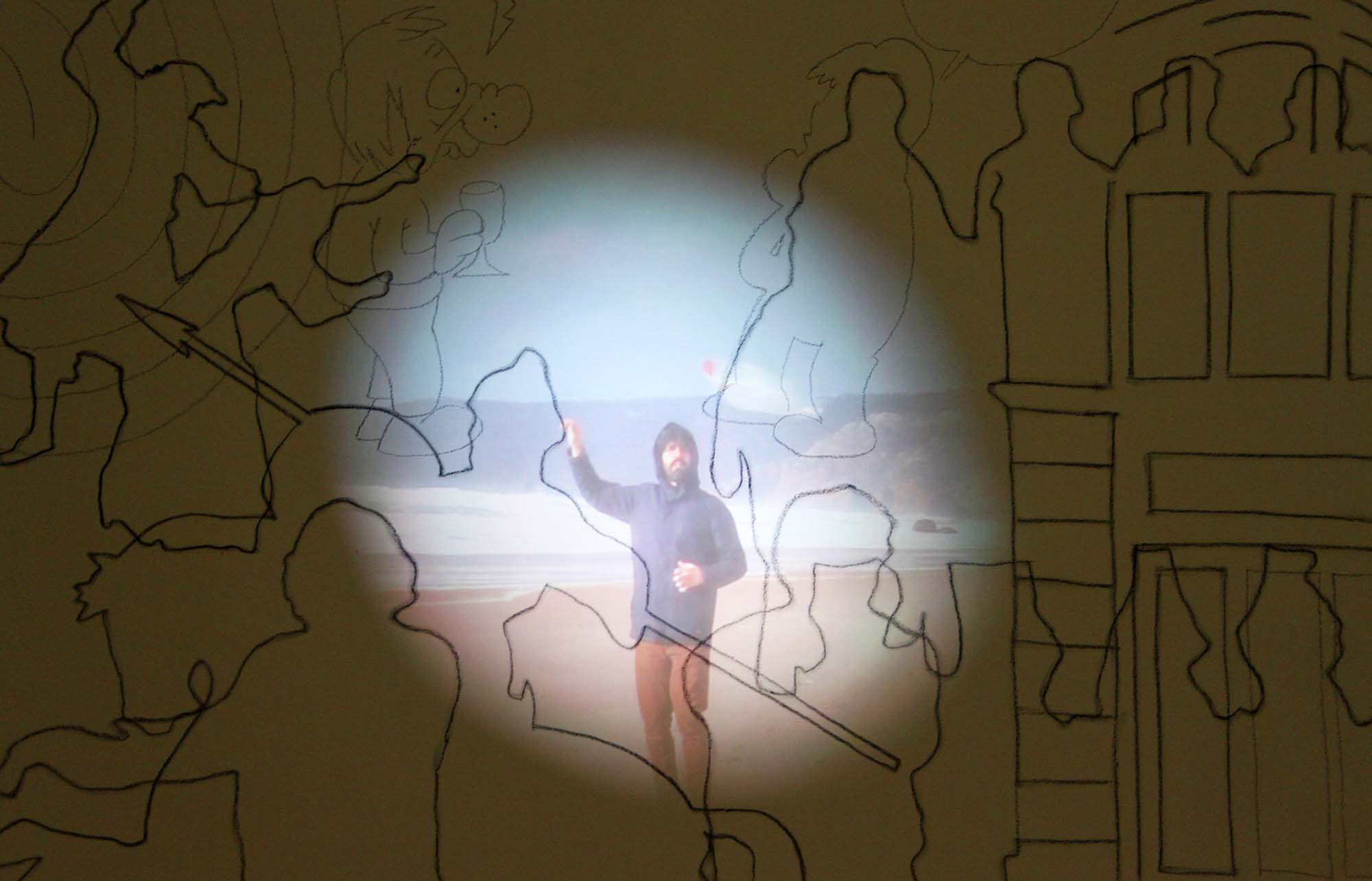

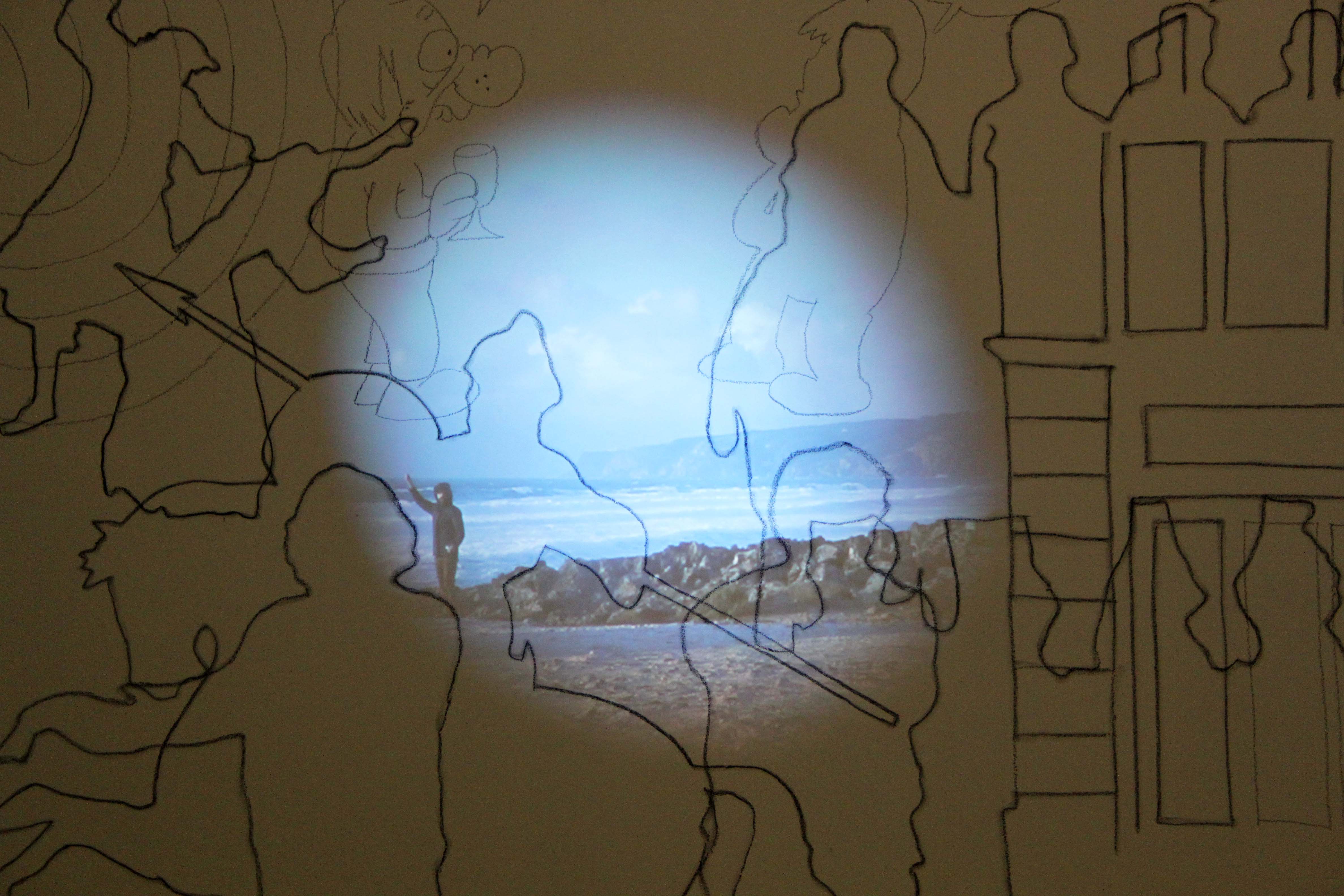

"Qu’est-ce que j’peux faire? Je ne sais pas quoi faire!", 2016 (Charcoal on Wall. Variable dimensions.) The French phrase “What is to be done? I do not know what is to be done!” Is mumbled by Anna Karina in Jean-Luc Godard’s “Pierrot, le fou” (1965). The drawings were first found in google images, which transforms any word into images. Following the random selection of google, the images were drawn directly from the computer screen. The mural results from an overlapping of images resulting from the transformation of the words that make up the phrase (and that gives title to the work) in images. The result is a charade: how to read? how to think? what to do?

"La Jetée", 2016 (Lambda photography). 70 x 50 cm. “La jetée” makes a reference to the photo-film of Chris Marker (1962). The terraces of the Orly Airport, Paris, were during the years following its construction the most visited monument in the world (it was followed by the current tour leader, the Eiffel Tower). Tourists fascinated by the brand-new modern cathedral came to watch the planes take off in an admirable modern spectacle. In 1975, the attack of the terrorist Carlos, the “jackal”, closed the famous terraces and put an end to a happy era, that the singer Gilbert Bécaud immortalized with the popular song “The Sundays in Orly” (1963). The terraces reopened in the early 2000s, after a variety of security measures were adopted. In 2016, they closed again for renovation, and then were occupied by homeless, who found in this place a warm refuge abandoned by all.

« "Conjugation of a reflexive verb" »

- Paris, 2016

- Video, 3 x 12’

- Suicides: Eduardo Jorge and âfs

- Camera: Antoine de Mena

- Editing: Antoine de Mena and âfs

- Sound: Jonathan Lucas

Conjugation of the verb “suicidar-se” [to commit suicide] following the convention stipulated by Celso Cunha and Lindley Cintra in “Nova Gramática do Português Contemporâneo” [New Grammar of Contemporary Portuguese] (1984).